Mapping Segregation in Washington DC reveals the role of race in shaping the nation's capital during the first half of the 20th century.

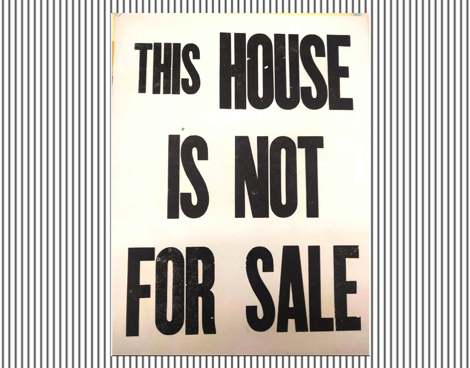

Racially restrictive covenants—which barred the conveyance of property to African Americans—were used by real estate developers and White citizens associations to create and maintain racial barriers. Upheld by the courts, covenants assigned value to housing and to entire neighborhoods based on the race of their occupants, and made residential segregation the norm. Federal policy and local zoning codes served to institutionalize segregation and the displacement of Black residents. As shown in this project’s story maps, segregated housing projects, schools, and playgrounds also helped create exclusively White neighborhoods and concentrate Black residents in areas that were older and overcrowded or remote and less developed.

Although eventually outlawed, racial covenants had a lasting imprint on the city. Their association of Whiteness with higher property values led to decades of disinvestment in areas where most Black residents lived. Their legacy remains visible in the unequal distribution and quality of public resources such as parks, hospitals, and grocery stores and in the persistence of segregated neighborhoods and schools. Finally, by barring Black access to wealth-building through real estate, covenants contributed to today’s vast racial wealth gap in DC. By revealing the deliberate harm inflicted on Black Washingtonians via the use and enforcement of racial covenants and racist land use policies, this project is meant, in part, to serve as a resource for redress.

Mapping Segregation is a resource for historians, activists, educators, students, and journalists, and provides essential context for conversations around race and gentrification in DC. The project's maps unveil historical patterns that would otherwise remain invisible and largely unknown. The ongoing, lot-by-lot documentation of racial covenants is set in the context of DC's demographic transformation over the course of several decades. Primary documents, archival news clippings, photographs, and oral testimony also contribute to the stories these maps tell.

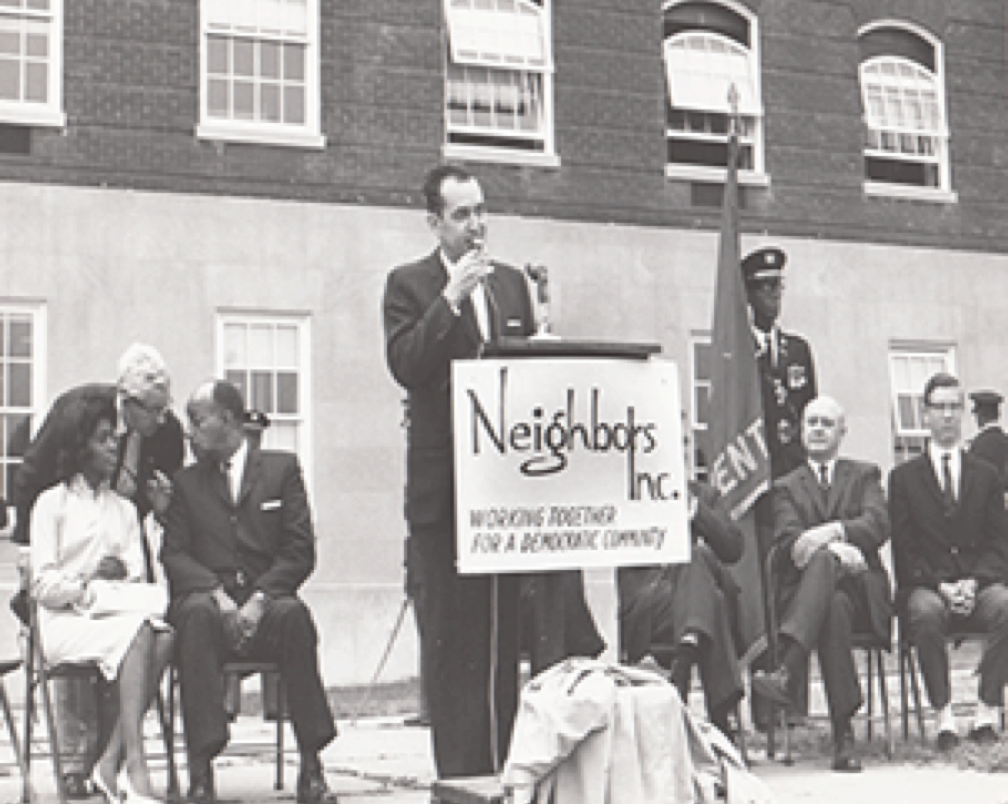

Conceived by historians Mara Cherkasky, Sarah Jane Shoenfeld, and Brian Kraft, this project has received funding from Humanities DC, the DC Preservation League, and the National Park Service. Kevin Ehrman-Solberg, Michael Corey, and Bliss Cartwright provided GIS and data support. Other supporters include All Souls Housing Corporation, the Military Road School Preservation Trust, the DC History Center, and Neighbors, Inc.

This website was produced with assistance from the Historic Preservation Fund, administered by the National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior.